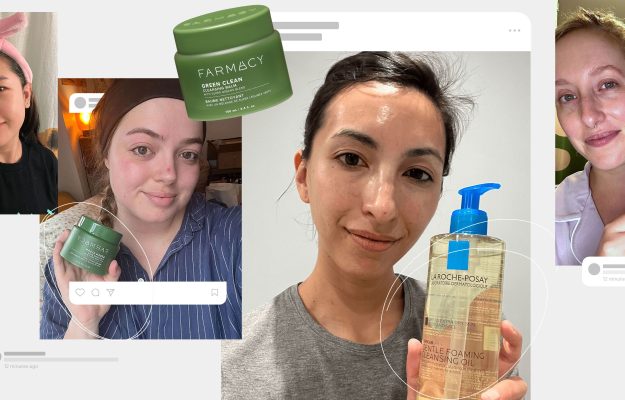

If You Don't Use Hair Oil, You're Missing Out

Their gloss-boosting formulas are mainstays in our editors’ routines.

BEAUTY

The Best White Tea Perfumes Smell Like an Expensive Spa Vacation

White Lotus, but for the pulse points.

BEAUTY

At 66, Andie MacDowell Would Love to Play a “Sexual Creature”

Casting directors, are you listening?

BEAUTY

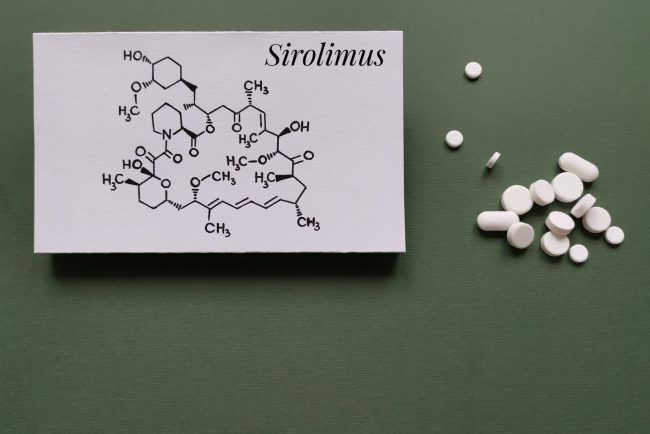

Which Blood Tests When Taking Rapamycin?

When taking rapamycin, and especially when starting with this drug, it’s important to keep track of some blood biomarkers that rapamycin could impact. First, tests that measure red and white blood cells levels to see if these are not declining. Rapamycin is an mTOR […]

ANTI-AGING

When taking rapamycin, and especially when starting with this drug, it’s important to keep track of some blood biomarkers that rapamycin could impact.

First, tests that measure red and white blood cells levels to see if these are not declining. Rapamycin is an mTOR inhibitor that impedes growth. Red and white blood cells are continuously produced at very high rates in the body, and in some people rapamycin could reduce the production of these cells.

This could lead to anemia (too little red blood cells) or leukocytopenia (too little white blood cells).

For example, a physician started to take 6 mg or rapamycin once weekly for longevity, but after a few months his red blood cell values started to go down. He decided to take 6 mg twice-weekly, and his red blood cell levels normalized again and didn’t go down ever since.

People also check their sugar metabolism: rapamycin might increase glucose levels and induce insulin resistance. However, keep in mind that increased glucose levels or insulin resistance is not always a bad thing in the context of taking rapamycin, as I explained earlier.

Nonetheless, it can be useful to keep track of sugar metabolism biomarkers, such as fasting glucose, fasting insulin and HbA1c, for example every 3 to 4 months, to see if rapamycin does not increase insulin resistance (in most people it won’t).

Overview lab work for rapamycin

Below you can find an overview of a blood panel done in patients taking rapamycin. It can be done every 3-4 months, especially in the beginning of the treatment.

Red and white blood cell levels and platelet count

– Red blood cell count

– Hematocrit: the volume of red blood cells compared to the total volume of blood

– Mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH): the average amount of the oxygen-transporting hemoglobin in your red blood cells

– Mean corpuscular volume (MCV): the average size of your red blood cells

– Mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC): the concentration of hemoglobin in red blood cells

– Red blood cell distribution width (RDW): looks at how varied red blood cells are in size (being too big or too small)

– White blood cell count (WBC), including lymphocytes, monocytes, basophils and neutrophils

– Platelet count

Iron metabolism (required to make red blood cells)

– Iron

– Ferritin

– Transferrin

– Total iron binding capacity (TIBC)

Metabolism

– Fasting glucose

– HbA1c

– Fasting insulin (and eventually HOMA-IR score to measure insulin resistance).

– Fasting triglycerides

– Fasting total cholesterol

– Fasting HDL

– Fasting LDL

This might seem like a lot. But don’t panic: these biomarkers are often checked in standard blood tests. You could go to your doctor and ask to get these biomarkers tested.

You could also look for blood testing labs close to where you live; many of these labs also offer blood tests to non-medical individuals to check their health, without needing to see a medical doctor. Of course, these tests are then not reimbursed; testing for all the biomarkers above will set you back by around 70 to 90 dollars or euro.

One does not necessarily have to test for all of these biomarkers. The bare minimum would be the number of red blood cells, hematocrit, white bloods, fasting glucose, total cholesterol and LDL cholesterol.

A note: total cholesterol, HDL and LDL levels can suffice to track one’s response to rapamycin. However, as I will explain later on, there are better biomarkers to measure cholesterol metabolism and heart disease risk.

Before one starts taking rapamycin, one could do a biological age test, like an epigenetic test, to see if the rapamycin reduced one’s biological age after at least 6 months to a year. However, most epigenetic tests are not accurate enough (yet) to measure an individual intervention in one person.

The post Which Blood Tests When Taking Rapamycin? appeared first on Kris Verburgh.

Optimal Rapamycin Dose for Longevity and Anti-Aging

More and more people are taking rapamycin for longevity. However, there are still lots of misconceptions surrounding rapamycin. Some people think it’s a drug that can have significant side effects. First, there are reports that rapamycin can cause insulin resistance (R). However, this mainly […]

ANTI-AGING

More and more people are taking rapamycin for longevity.

However, there are still lots of misconceptions surrounding rapamycin. Some people think it’s a drug that can have significant side effects.

First, there are reports that rapamycin can cause insulin resistance (R). However, this mainly seems to be the case when rapamycin is taken in high doses and for a long-time (due to indirect sequestration of mTOR components that also belong to the mTOR2 complex).

Furthermore, the “high glucose” levels induced by rapamycin can also be due to “pseudo” diabetes, caused by the fasting-mimicking effect of rapamycin. I explained this more in detail earlier.

Another often-heard worry is that rapamycin is an immunosuppressant, used to prevent rejection of kidneys. Therefore, some people fear that rapamycin suppresses the immune system too much.

However, to prevent immune rejection, rapamycin is given in high, continuous (daily) doses, and together with other, far stronger (and unhealthy) immunosuppressants, such as cyclosporine and corticosteroids.

Kidney transplant patients are given a high loading dose of rapamycin of around 15 mg, and then receive a daily maintenance dose of 5 mg. Sometimes lower doses are given, such as a 6 mg loading dose followed by 2 mg of rapamycin per day.

When only rapamycin is taken (so no other, much stronger immunosuppressive drugs), various studies demonstrate that rapamycin can actually improve immune function. For example, rapamycin could reduce the risk of dying from infectious diseases, as I explained earlier.

Also, contrary to kidney transplant patients, who receive rapamycin daily, various longevity physicians recommend taking rapamycin only once-weekly or two-weekly.

So which rapamycin doses are taken for longevity?

Mostly, 2 mg to 10 mg of rapamycin is taken, every week or every two weeks.

Professor Michael Blagosklonny, an expert in rapamycin and longevity, even took a regimen of 20 mg of rapamycin every two weeks.

Generally, the most often recommended rapamycin dose is between 2 and 8 mg once weekly or every two weeks.

Mostly, people take 5 to 7 mg weekly.

Some experts recommend taking “rapamycin holidays”. For example, one takes rapamycin (bi)weekly for 3 months. And then takes a break of one month, during which one does not take any rapamycin, and then starts again a 3 month period (R). Other people take rapamycin for 3 months, and then take a 3-month break.

As you can see, such dose regimens are considerably lower and different than when taken in an organ-transplant context, in which rapamycin is taken daily, sometimes 5 mg or more per day, and in combination with other very strong immunosuppressants.

However, there have been longevity or health-focused studies in humans in which rapamycin is given continuously, demonstrating no serious side effects. In one study, a relatively low dose of 1 mg of rapamycin every day in elderly people (to improve immune function) didn’t lead to significant side effects and was shown to be safe (R).

In general, rapamycin has demonstrated to be a reasonably safe drug. Multiple clinical trials show that serious side effects are very low or non-existent. Some studies even show that side effects are higher in the placebo group than in the rapamycin treated group (R). In a failed suicide attempt one person took 103 tablets of 1 mg or rapamycin (so 103 mg in one go), with no significant side effects (only elevated cholesterol) (R).

However, when starting rapamycin treatment it’s important to keep some things in mind, such as closely following specific blood biomarkers.

The post Optimal Rapamycin Dose for Longevity and Anti-Aging appeared first on Kris Verburgh.

Shortcomings and Problems with Blood Lab Tests

Most people have a “normal” blood test, thinking they are healthy. Unfortunately, blood tests provide a crude and incomplete picture of our health. People can have “A ok” blood tests and still be deficient in many micronutrients, suffering from inflammation, a bad thyroid gland, […]

ANTI-AGING

Most people have a “normal” blood test, thinking they are healthy.

Unfortunately, blood tests provide a crude and incomplete picture of our health.

People can have “A ok” blood tests and still be deficient in many micronutrients, suffering from inflammation, a bad thyroid gland, an unhealthy microbiome, pre-diabetes, increased genomic instability (e.g. an increased risk of double strand DNA breaks), fatty liver, a deregulated epigenome, accelerated aging, or many other problems.

To make a long story short: a blood test often provides only a limited, crude snapshot of our health.

Many commonly used blood biomarkers are not ideal to screen for diseases or problems. For example, measuring total, LDL and HDL cholesterol are not the best tests to assess cardiovascular risk.

And various biomarkers, like magnesium or B vitamin levels, are not a correct reflection of the real levels in your cells.

Nonetheless, blood tests still can be useful. But it’s important to interpret these tests with some reservations and caveats, and be mindful of their limitations.

There are various problems with blood tests. I list the most important ones below:

1. Cut-off values are not always ideal

Blood biomarkers have cut-off values: you should not have too much or too little of a specific substance in your body.

For example, you should have at least x mg/dl of vitamin y in your blood. If you have less than that, you are deficient.

However, these cut-off values are often “determined” in a crude way; based on old or inaccurate or crude measurements or studies.

Also, many cut-off values are derived by just looking at the “reference ranges” of the substance in a population.

So scientists look at which values are present in 95% of the population, and then determine these are the “good”, “healthy” or “required” values or levels.

But what if many people of the population are deficient in the nutrient? Then these cut-off values are based on a sick or unhealthy population.

Also, these values would not say much about the best or ideal blood levels for a long, healthy life. As mentioned before, for tens of thousands of years, people just had to stay alive long enough to reproduce. If a mild deficiency does not interfere too much with this in the first three decades or so of life (but would come back to bite you after five or six decades, when you are old, increasing the risk of cancer, heart disease or Alzheimer’s) then having these “suboptimal” values is still ok for mother nature.

Another problem is that these reference ranges or cut-off values are specific to populations (e.g. the diagnostic lab using reference ranges from the people who live close to the laboratory/got tested there), the device (some devices measure higher or lower levels compared to other devices), and the laboratories (their specific protocols and handling of the samples and machines).

Also, age, smoking status, medication, sex, circadian rhythms, weight, and ethnicity can impact the values of many biomarkers, but are hardly or never taken into account (R).

These insights explain why, over the decades, cut-off values had to be adjusted because the FDA realized that these values were too restrictive.

For example, not so long ago, only when you had vitamin D levels lower than 20 ng/ml you would be considered deficient. But then these cut-off values were increased to 30 ng/ml, while studies seem to indicate that ideal vitamin D levels for longevity could be even higher.

Another example is TSH (thyroid stimulating hormone). A too high level of TSH means your thyroid is not working properly (it’s too slow). Many labs will say your thyroid is not functioning well when TSH levels are higher than 4 mIU/L. However, many doctors disagree with this, claiming that TSH levels should be maximally 2.5 mIU/L. Nonetheless, most labs will still use the 4 mIU/L cut-off value.

2. Blood levels of many biomarkers fluctuate

The blood levels of many substances can fluctuate significantly during the day. If you just happened to get measured when levels are high (while most of the time being low), it could be wrongfully interpreted that there is no problem.

Examples of substances that fluctuate a lot are cortisol, hormones like testosterone, TSH, IGF (insulin like growth factor), and so on.

Some MDs try to solve this by measuring substances over time. So instead of measuring cortisol only once in the blood (not useful in most cases), they measure 24-hour secretion of cortisol in the urine. Such a test is more accurate, but still not perfect.

3. Various biomarkers cannot be properly measured

This is especially relevant for vitamins and minerals like magnesium, calcium, potassium, vitamin E, and so on. In most cases, these are measured in blood, not in the cells or in the fluid between the cells outside of the bloodstream (the interstitial fluid), where these nutrients are often present in different levels.

Furthermore, many minerals, vitamins and other substances are bound to proteins that transport them in the blood. So only the levels of the free floating substances (not bound) are measured (or one measures only the bound forms, not the free, active forms).

For minerals like calcium, potassium, magnesium, and vitamins, their values are often “normal” according to your blood test, while levels can be too low in the cells, or in specific tissues (like the brain).

Another example is vitamin B12. To “detect” vitamin B12 deficiency, this substance is often measured in the blood. However, people can have normal vitamin B12 levels and still be deficient. It can be more accurate to measure methylmalonic acid (MMA), which is a breakdown product of vitamin B12 (R).

Even better, the ratio of methylmalonic acid compared creatinine (so the methylmalonic/creatinine ratio) is measured, and homocysteine levels (R).

But even these measurements are not perfect. One can still be deficient in vitamin B12, while having a normal methylmalonic acid/creatinine ratio and normal homocysteine levels.

Therefore, it’s very important to also look at the complaints patients have; and perhaps to try a treatment with vitamin B12 to see if symptoms improve.

Another example is vitamin E. When measured in the blood, most people have “adequate levels of vitamin E.

However, if scientists actually look at what people eat (and calculate how much vitamin E they consume through their nutrition), around 90 percent of people do not reach the recommended daily intake of vitamin E (!).

And take into account that such “recommended daily amounts” that governments put forward are often still too low. They are all too often the minimum amount to not get seriously ill, or of which the consequences of a deficiency are measured with crude tools.

Or take potassium. The FDA recommends consuming at least 4,7 grams of potassium per day (in prehistoric times however potassium intake was more around 7-15 grams per day). Unfortunately, most people consume only around 2.5 grams of potassium per day.

However, in nearly all people potassium levels will be normal. Potassium levels mostly only are abnormal when very serious problems are going on, like kidney failure (or potassium levels can be “falsely” too high because the red blood cells in the blood sample are damaged, releasing potassium, leading to falsely elevated “blood” potassium levels).

So despite most people having normal vitamin E, vitamin B12, magnesium or potassium levels most people are deficient in these.

Learn more about the best supplements here.

4. Various biomarkers are not accurate to predict disease

Often, one relies too much on blood biomarkers to diagnose or dismiss a disease.

For example, to diagnose a thyroid problem, TSH (thyroid stimulating hormone) is measured. But TSH is not an ideal biomarker for thyroid disorders (R). TSH levels can often be normal, while one still has a deficient or malfunctioning thyroid.

Therefore, some doctors propose to do an iodine challenge test, in which people have to consume a large amount of iodine, and then during 24 hours the amount of iodine secretion is measured in the urine (if it’s too low, this could point to a thyroid problem).

Other MDs also look at antibodies against the thyroid gland, like anti-TPO and antithyroglobulin antibodies. Interestingly, people can have antibodies against their thyroid gland but still have normal TSH levels.

In such cases, most doctors will say there is no problem. But having anti-thyroid antibodies does already indicate a problem. The thyroid gland is being damaged, and will likely be further damaged, until the damage is so bad that lab tests will finally detect a problem (or not, given TSH levels are not that specific).

5. Many important substances cannot or are not measured

Most blood tests are far from complete and comprehensive.

Many important substances are not measured, or cannot be (properly) measured. For example, in most blood tests, one does not measure choline, omega-3 fatty acids, vitamin B6, vitamin B1, specific minerals and so on.

Also, more interesting, useful biomarkers, like DNA damage (e.g. double strand breaks), epigenetic dysregulation, or the amount of senescent cells (“senescent cell burden”) are not measured. These are interesting tests, but are not part of standard testing and are often too complicated or expensive.

So despite having had a blood test, many substances are not tested for, providing an incomplete picture.

6. Cut-off values are interpreted too narrowly

What if you are just one unit under or above a cut-off value? Do you have the disease or not?

For example, you are officially pre-diabetic when your fasting glucose levels are above 100 mg/dl (5.6 mmol/L). So if your value is 97 mg/dl, you are “healthy”?

Not really; elevated “normal” fasting glucose levels (e.g. of 95 mg/dl) could already be indicative of cardiovascular problems for example (R) (and an increased risk of dementia). So “high-normal” (or “low-normal”) levels can already be harbingers of trouble.

Therefore, interpret blood tests knowing that “where there is already some smoke, there is often fire”.

7. Cut-off values can be too lenient

A while ago, you only had problems with your blood sugar when your fasting blood glucose levels were above 126 mg/dl (7.0 mmol/L). Then the concept of pre-diabetes was introduced: you already have a significantly increased risk of diseases if glucose levels are higher than 100 mg/dl.

Now we see that levels even lower than 100 mg/dl can increase risk of diseases.

And one can still be at an increased risk of dying when fasting glucose levels are completely normal (not just “high normal”). After all, there are more accurate tests to diagnose insulin resistance.

The post Shortcomings and Problems with Blood Lab Tests appeared first on Kris Verburgh.

How Does Rapamycin Work? How Can It Slow Aging And Extend Lifespan?

Rapamycin can slow aging and extend lifespan in various ways. 1. Rapamycin is an mTOR inhibitor First, rapamycin is an mTOR inhibitor. mTOR is a protein found in our cells. It’s an important “nutrient” sensor which recognizes nutrients, mainly amino acids (but mTOR can […]

ANTI-AGING

Rapamycin can slow aging and extend lifespan in various ways.

1. Rapamycin is an mTOR inhibitor

First, rapamycin is an mTOR inhibitor. mTOR is a protein found in our cells. It’s an important “nutrient” sensor which recognizes nutrients, mainly amino acids (but mTOR can also sense glucose, cholesterol and oxygen levels). If there are a lot of nutrients, especially amino acids, present in our blood and cells (because we ate a big steak for example, which consists of proteins that are made up of amino acids), these activate mTOR. mTOR then revs up the production of protein (mainly, but also of DNA and lipids), and increases metabolism and growth in our cells.

This all makes sense. If there are a lot of nutrients (e.g. amino acids) available, this means there are a lot of building blocks and energy available for our cells, so the cells rev up their metabolism and growth.

However, this also has a downside. This activation of metabolism and growth accelerates aging of cells. Cells start to produce more proteins, which can clump together faster, contributing to aging (accumulation of proteins is one of the causes of aging).

More scientifically speaking, mTOR activates various important proteins (by putting a phosphate group on them) involved in protein production, like S6K and 4E-BP (eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E-binding protein).

Another consequence of having lots of nutrients available is that cells will maintain themselves less well. They let themselves go. Why should they be frugal and painstakingly recycle their components and maintain and repair themselves, when there are enough building blocks and energy available? No need to skimp on repair, recycling and maintenance with an abundance of resources.

Compare it with money; some people who suddenly have lots of money splurge on all kinds of things they don’t really need, spending it quickly; living the fast life. On the other hand, some people who have little money will live more frugally, be careful what to spend, and rather recycle stuff for their home and repair things instead of buying new things.

How does mTOR activation cause less maintenance? It suppresses autophagy, which is an important maintenance and recycling process. Autophagy is the breakdown (digestion) and recycling of proteins and other cellular waste material. mTOR-induced suppression of autophagy causes more build-up of (damaged) proteins, old and damaged cell components (like mitochondria), and other problems. If you eat lots of protein, especially animal-based protein, mTOR is activated and autophagy is suppressed. mTOR inhibits autophagy by phosphorylating proteins involved in autophagy, like ULK1.

The opposite happens when we are eating little (e.g. during fasting): autophagy is then upregulated, which cleans up the cell and increases maintenance and lifespan. The cell has to use its resources wisely because it doesn’t know when there will be food again.

Rapamycin inhibits mTOR, leading to reduced protein production. This leads to less protein clumping, one of the hallmarks of aging.

Rapamycin induces autophagy, which causes cells to maintain themselves better: they clear up protein accumulation (protein aggregates), thus reducing proteotoxicity.

Interestingly, rapamycin can also induce autophagy independent of mTOR. Rapacymin stimulates an important channel on the lysosomes (TRPML1), which activates lysosomes (R). The lysosomes are small vesicles in our cells which break down proteins and old or damaged cell components – you can consider them as the incinerators of the cells (I explain more about lysosomes and autophagy in the earlier chapter the hallmarks of aging, namely a decline in proteostasis).

2. Rapamycin improves mitochondrial health

Rapamycin can also be promising to treat mitochondrial diseases.

Rapamycin has been shown to improve mitochondrial health, both in normal mice (R) and in mice with serious mitochondrial diseases (R,R,R,R).

In one mitochondrial disease model, called Leigh’s syndrome, rapamycin was given to see if it could improve survival of mice with this disease. Leigh’s syndrome is a very serious mitochondrial disorder caused by a defective protein in the mitochondrial respiratory chain.

This is a very important chain of proteins through which electrons flow (coming from the food you eat, which are then donated to the oxygen molecules you breathe in to form water); this flow of electrons drives the ATP generator proteins studded on the inner membranes of our mitochondria, generating ATP, which is the molecule of life, providing energy for most metabolic processes.

The mitochondrial respiratory chain generates nearly all the energy of the cell, and thus for life to sustain itself. In Leigh’s syndrome, a protein in this chain is not working properly, severely impeding the ability of cells to produce energy. In these mice, rapamycin extended lifespan up to threefold (R).

How can rapamycin improve mitochondrial health?

For one thing, rapamycin upregulates lysosomal function. Lysosomes are small cell components which break down cellular waste and even whole cell components, like the mitochondria. Each cell can contain hundreds or more mitochondria, which provide the energy cells need to function. These mitochondria, when they are too damaged or worn out, need to be broken down and replaced by new mitochondria. Mitochondria are broken down in the lysosomes, the little incinerators of the cell.

Rapamycin induces the lysosomes to break down mitochondria so that worn-out mitochondria are more replaced with fresh and better functioning mitochondria. Rapamycin can also activate lysosomal biogenesis (the creation of more lysosomes), which is a good thing given cells then get cleared out and maintained better by additional lysosomes (R,R).

3. Rapamycin has epigenetic effects

Rapamycin also impacts the epigenome, and can reduce epigenetic age (R,R). The epigenome determines which genes are switched off and on in our cells, and during aging this mechanism goes awry.

Rapamycin can improve the epigenome in a beneficial way, for example by inducing the expression of beneficial genes (R,R,R).

4. Rapamycin improves the microbiome

The gut microbiome are the bacteria in our intestines. These 40,000 billion bacteria have a big impact on our health and well-being, for example by processing and secreting thousands of substances, of which many enter our bloodstream and impact our immune system, metabolism, and brain, among many other things.

However, during aging, the microbiome deteriorates, leading to bacterial overgrowth, increase of “virulent” (bad) bacteria, and damage to the gut lining (“leaky gut”).

Rapamycin can positively impact the bacterial diversity in the gut or inhibit nefarious bacterial activity. In one study in mice, rapamycin increased the amount of segmented filamentous bacteria, which are “good” bacteria that do not tend to secrete unhealthy substances and strongly cling onto the gut wall, which strengthens the gut lining and positively impacts the gut immune system (R).

Interestingly, another well-known longevity-candidate, metformin, has also been shown to significantly impact the microbiome, by also modulating or tempering bacterial activity in the gut. I discuss metformin for longevity later on.

5. Rapamycin reduces inflammation

During aging, inflammation gradually increases everywhere in our body. This is called “inflammaging”, and this condition is one of the hallmarks of aging.

Rapamycin reduces inflammation. It inhibits the products of various proinflammatory proteins, like NfkB and interleukins (R), and can modulate the immune response in a beneficial way (R).

Rapamycine can also reduce the unhealthy “secretory phenotype” of senescent cells; these cells accumulate during aging and secrete various unhealthy, pro-aging substances, like pro-inflammatory substances. This is why rapamycin is also called a “senomorphic”, being able to change the way senescent cells behave, as contrary to “senolytic”, which is a drug that kills senescent cells (the problem however with many senolytics is that they can also kill or damage normal, healthy cells).

6. Other effects of rapamycin on health

Given these and other effects of rapamycin on the body, it’s not surprising that rapamycin can improve stem cell health (R), reduce senescence (R), and extend lifespan, among other effects.

Learn more about rapamycin:

- Does Rapamycin Cause High Glucose, Lipids and Diabetes?

- Does Rapamycin Increase Infection Risk?

- How Does Rapamycin Work? Overview of Rapamycin Lifespan Extension Studies

- Rapamycin for Anti-Aging and Longevity

- How does rapamycin work? How can it slow aging and extend lifespan?

The post How Does Rapamycin Work? How Can It Slow Aging And Extend Lifespan? appeared first on Kris Verburgh.

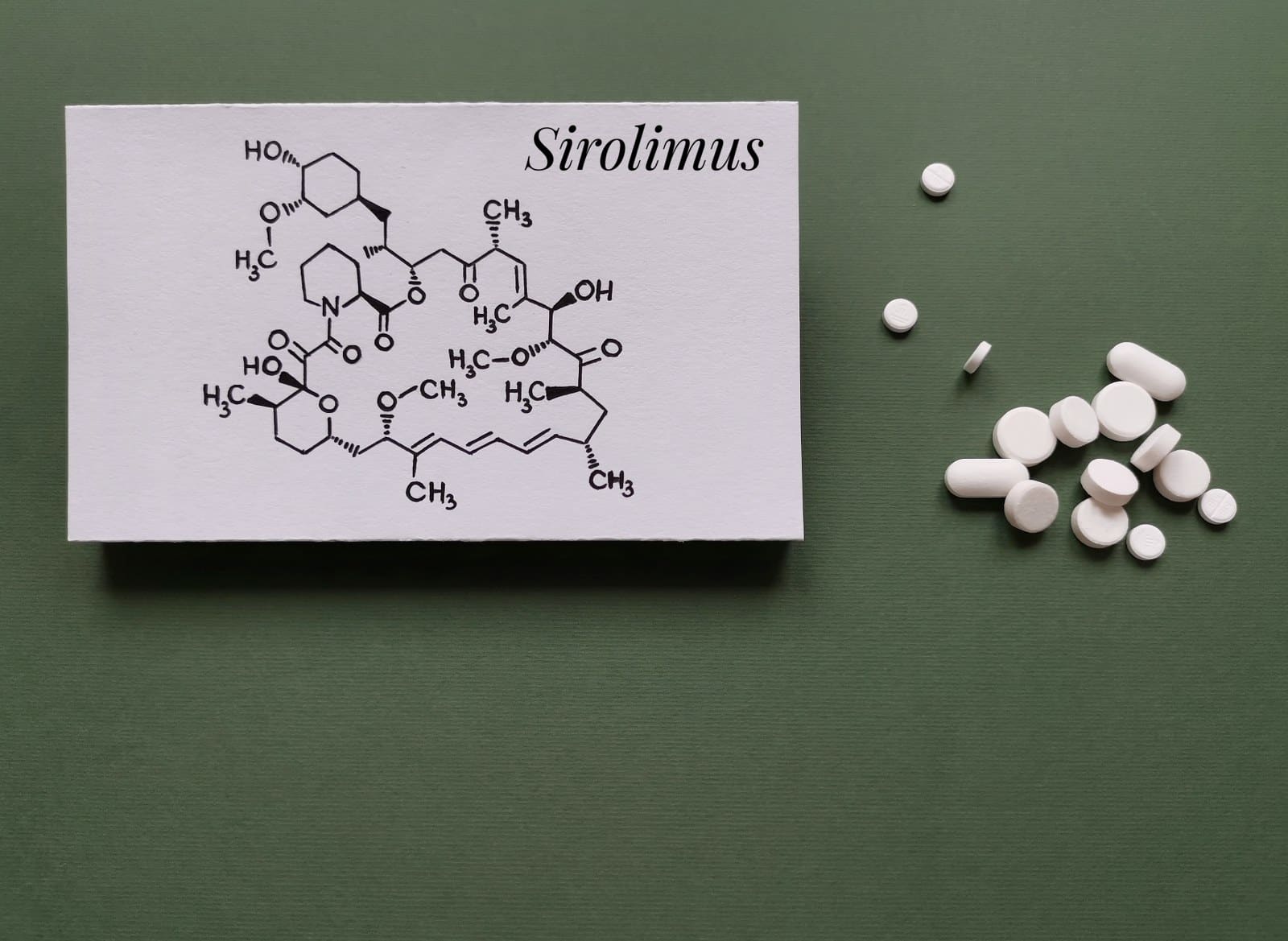

The Food Hourglass Longevity Diet

Why a longevity diet is the best diet There are hundreds of different diets, thousands of diet books, and innumerable diet coaches and gurus all claiming they have the ultimate diet. Especially the internet is a jungle of different diets and contrary nutrition advice. There […]

ANTI-AGING

Why a longevity diet is the best diet

There are hundreds of different diets, thousands of diet books, and innumerable diet coaches and gurus all claiming they have the ultimate diet.

Especially the internet is a jungle of different diets and contrary nutrition advice. There are meat-based diets, fat-fueled keto diets, low carb and vegetarian diets. There are diets named after doctors who (re-)invented them, like the Atkins diet, Dukan diet, or Dean Ornish diet.

So how to see this wildly overgrown forest for the trees? How can we find out what the best diet is?

To find out what the best diet is we need to approach diets, and nutrition in general, in a new way: by basing ourselves on the science of aging. Knowing why we age helps us to provide far better diet and nutrition advice.

For example, knowing that proteins play an important role in the aging process, a high-protein diet might not be a good idea in the long-term, despite achieving lots of weight loss in the beginning.

So what is the best diet out there? The best diet is a diet that slows down aging. A longevity diet.

Given a longevity diet acts on fundamental processes of aging, such a diet reduces the risk of aging-related diseases such as heart disease, cancer and Alzheimer’s, given aging is the main driver of these diseases.

A nice bonus is that a longevity diet also leads to weight loss if one is overweight. Without having to count and restrict calories.

The Food Hourglass Longevity Diet

I developed the Food Hourglass Diet using the latest insights into aging. It focuses on slowing aging and increasing longevity.

The upper part of the Food Hourglass contains foods that are more unhealthy and one should eat less of, like red meat, starchy foods, and unhealthy fats.

The lower part contains healthy foods one should eat more of, like vegetables, legumes, white meat, fish, or mushrooms.

Thanks to the hourglass shape, one can easily see how to replace unhealthy foods with healthier alternatives.

For example, red meat (pork, beef, lamb) in the in the upper part of the Food Hourglass can be replaced with the healthier alternatives in the lower part, namely white meat (poultry), fatty fish, eggs, fungi-based meat alternatives (e.g. Quorn), tofu, or mushrooms.

Starchy, empty-calorie foods like bread, potatoes, pasta and rice in the top part of the Food Hourglass can be replaced with vegetables, legumes and mushrooms in the lower part.

Unhealthy oils (e.g. omega-6 rich like corn oil, sunflower oil, palm oil, sesame oil) in the upper part can be replaced by healthier alternatives, like olive oil or walnut oil.

You can download an image of the Food Hourglass at the bottom of this article.

The Food Hourglass Diet can be summarized in 9 simple rules.

The 9 rules of the Food Hourglass Diet

1. No or very little sugary foods

This means no or very little candy, snack bars, cookies, cake, pastry, soft drinks. Substitute these sugary foods with healthier alternatives, such as:

– Dark chocolate (70% cacao or more)

– Fruits: apples, pears, blueberries, strawberries, cherries, peaches, etc.

– Nuts: walnuts (rich in omega-3 fatty acids), hazelnuts, almonds (rich in vitamin E), cashews, etc.

– Low-sugar desserts: almond yogurt, soy yogurt, coconut yogurt.

2. Less starchy foods

Replace as much as possible bread, potatoes, pasta and rice with:

– Vegetables

– Legumes: beans, peas, lentils

– Mushrooms: shiitake, portabella, oyster mushrooms, etc.

– Quinoa.

So instead of potato mash, consume broccoli mash.

Instead of rice, consume Cannellini beans.

Instead of pasta, consume oyster mushrooms.

Bread in the morning can for example be replaced with:

– Healthy porridges: chia seed porridge, cauliflower-banana porridge, low-sugar oatmeal porridge, etc.

– Breakfast bowls: for example, a bowl containing blueberries, snippets of avocado, quinoa flakes mixed with vegetable milk or plant-based yogurt (low-sugar almond yogurt, coconut yogurt, soy yogurt, etc.)

– Other healthy breakfast alternatives: more coming soon. My new book on longevity will also contain healthy recipes for longevity).

3. Vegetables and legumes are the basis of a longevity diet, not starchy foods

Vegetables (especially) and legumes are the basis of a healthy longevity diet, not potatoes, pasta, rice or bread.

If you do want to eat now and then starchy foods, try to consume:

– Gluten-free products (even if you are not coeliac, gluten is a protein in grains that can damage the gut lining and be immunogenic): gluten-free pasta, gluten-free bread, or rice (which does not contain gluten anyhow).

– Whole-grain products: e.g. whole-grain pasta, and brown or black rice (not white rice).

– Resistant-starches: after cooking, let starchy foods (potatoes, pasta or rice) cool down in the refrigerator for a few hours or overnight, and then reheat them. The cooling-down process “crystallizes” the starches and turns them into healthy “resistant starch”, which causes considerably less high sugar peaks. Resistant starch is in fact a fiber which nourishes healthy bacteria in the gut, among other things.

4. Replace red meat with white meat, fish and meat alternatives

Replace red meat (pork, beef, lamb) with:

– White meat: poultry like chicken or turkey

– Fatty fish: salmon, herring, mackerel, anchovies, sardines

– Meat substitutes: tofu, miso, natto, tempeh, mushrooms, fungi-based meat substitutes (e.g. Quorn), plant-based meat substitutes, eggs.

5. Consume more healthy fats

– Consume more foods containing healthy fats, like olives, olive oil, nuts, chia seeds, flax seeds, fatty fish, fish roe, avocado, etc.

– Avoid unhealthy fats, like trans fats and omega-6 rich fats, found in margarine, corn oil, sunflower oil, salad oils, dressings, fried foods, fast foods (pizza, hamburgers), etc.

6. Drink mostly water, with some tea, coffee, little or no alcohol

– Don’t drink (diet) soda or store-bought fruit juices

– Drink mostly water. You can flavor water with lemon (juice), mint, or infused fruits.

– Tea: one to a few cups of green, white or black tea per day. These teas contain caffeine, and tend to invigorate. Chamomile tea does not contain caffeine and helps to relax (e.g. great to drink before bedtime).

– Coffee: maximum 1-3 cups per day, not in the afternoon given the quarter-life of coffee is about 12 hours, meaning after this time there is still 25% of caffeine left in your system

– Optional: a smoothie made of low-glycemic index fruits (e.g. blueberries, blackberries, strawberries) and vegetables, or ideally only vegetables

– No or very little alcohol. If you must, consume maximum one glass of alcohol per day with alcohol-free days

– Consume lots of soups, including cold soups

– Make sure you drink enough, at least 2 litres (68 ounces, 0.5 US gallon, or 8 glasses) of fluids per day, mainly water.

7. No animal milk and yogurt, and little diary such as cheese

– Replace animal milk with low-sugar plant-based milk: almond milk, hazelnut milk, cashew milk, soy milk, etc.

– Replace animal-based yogurt with low-sugar plant-based yogurt, such as almond yogurt, soy yogurt, coconut yogurt, etc.

– Cheese in moderation, or no cheese: many people are (un)knowingly intolerant

– Take calcium supplements to make sure you consume enough calcium (divided over two doses of 500 mg per day, e.g. 2 x 500 mg of calcium per day; too much calcium at once can contribute to calcification of the arteries).

8. Consume more herbs and other healthy flavor enhancers

– Consume lots of herbs, such as turmeric, thyme, rosemary, parsley, oregano, mint, etc.

– Consume more vinegar

– Replace unhealthy oils (corn oil, sunflower oil, palm oil, salad oils, margarine) with healthy oils, such as olive oil for warm dishes, and flaxseed oil, walnut oil and olive oil for cold dishes

– Replace your normal salt (sodium chloride) more with potassium salt (potassium chloride, e.g. LowSalt – not sponsored).

– Replace sugar with healthy sugar substitutes, like stevia, monk fruit, sugar alcohols (xylitol), tagatose, (mashed) fruits (e.g. applesauce, banana mash).

Do not replace sugar with (organic) honey, maple syrup or agave: these still consist mostly of sugars (glucose, sucrose, fructose).

Do not replace sugar with artificial sweeteners (e.g. acesulfame, aspartame, saccharin, sucralose).

9. Take smart longevity supplements and health supplements

– Longevity supplements (to slow down aging): e.g. glucosamine, alpha ketoglutarate, fisetin, chondroitin, etc.

Learn more about the best longevity (anti-aging) supplements here.

– Health supplements (to prevent common deficiencies): e.g. magnesium, zinc, iodine, B vitamins, omega-3 fatty acids, etc.

Learn more about the health supplements everyone should take here.

Main principles of a longevity diet

This is in a nutshell what the Food Hourglass Longevity Diet is all about. The main take-aways are the following:

- Consume far less sugary and starchy foods (including bread, potatoes, pasta and rice), and much more vegetables, legumes, and mushrooms.

- Consume less unhealthy fats from (salad) oils, dressings and fried foods, and more healthy fats from olives, olive oil, avocado, nuts and seeds.

- Replace red meat (beef, pork, mutton) as much as possible with white meat (poultry), fatty fish, plant-based protein sources (e.g. legumes, mushrooms, broccoli), and fungi-based meat alternatives (mushrooms, Quorn, tofu, etc).

If you follow a diet like this, you will

1) slow aging and significantly reduce your risk of aging-related diseases, like heart disease, type 2 diabetes, cancer, Alzheimer’s and many other diseases;

2) lose weight if you are overweight;

3) feel better: feeling less tired, brainfogged, or sad, having more energy, being more motivated, being able to think more clearly, sleep better, among many other things.

If you follow a longevity diet, you do not need to count calories, jo-jo between weird diets, eat large quantities of protein (like in high-protein diets) or fats (like in keto diets), or to completely avoid animal foods (like with a vegetarian or vegan diet).

Many of these diets can actually accelerate aging in the long term (in the short-term, most diets “work”, in the sense one loses weight or feels better).

Later on I will discuss the shortcomings (but also good points) of these popular diets, especially high-protein (meat-based) diets, keto diets and vegetarian diets. These diets have some good and bad points, which explains why so many people hold (very) strong opinions about these diets.

I will approach these diets from a longevity (biogerontological) angle so we can better understand what these diets do with our body, and what their effects are on the long term.

Using insights from the aging process, we can better see why these diets, which often do work in the short term (you lose weight and often you do feel better), can actually accelerate aging in the long term.

You can download the Food Hourglass image below, print it, and put it on your fridge.

Or share the pdf file with friends and family!

The post The Food Hourglass Longevity Diet appeared first on Kris Verburgh.

Pros and Cons of Cancer Screening Tests like Galleri

Cancer is the second cause of death, right after cardiovascular diseases (such as strokes and heart attacks) in most developed countries. Cancer is a dreadful disease. In my new, upcoming book on longevity, I explain how cancer originates and how to better treat and […]

ANTI-AGING

Cancer is the second cause of death, right after cardiovascular diseases (such as strokes and heart attacks) in most developed countries.

Cancer is a dreadful disease. In my new, upcoming book on longevity, I explain how cancer originates and how to better treat and prevent it.

But detecting cancer at an early stage is also a very important aspect of not dying from cancer.

Current cancer treatments are very taxing and detrimental to the body, not only damaging cancer cells, but also healthy cells and tissues, as happens with chemotherapy, radiation and surgery.

Therefore, it’s crucial to prevent cancer, and if it does arise, to detect cancer early, so the patient has a much better likelihood of being cured.

When a cancer is diagnosed early, before it has had the chance to spread, the 5-year survival rate is 4 times higher than when diagnosed at a later stage:

For various cancers, chances of survival are more than ten times higher when detected at an early stage (stage 1) versus a later stage (stage 4), especially for liver, lung and pancreas cancer:

To screen for cancer, there exist two main categories of tests:

– Multi-cancer early detection tests: which screen for multiple cancers at the same time. An example is the Galleri test.

– Single-cancer early detection tests: these tests focus on one specific kind of cancer, like colon cancer or cervix cancer.

Let’s start with multi-cancer early detection tests (MCEDS).

Multi-cancer early detection tests (MCEDS)

These tests screen for multiple cancers. A blood sample is drawn. This test looks for traces of cancer, such as circulating tumor DNA, which is DNA that tumor cells release into the blood.

This circulating DNA coming from cancer cells is somewhat mutated, or has epigenetic changes, meaning it’s methylated differently (different arrangements of methyl groups on the DNA) or is histonylated differently (the DNA is wrapped differently around histones, which are proteins around which the DNA strand is wrapped).

Specific diagnostic machines can measure this mutated, cancer-derived DNA from a blood sample. Some tests also look at other substances which cancer cells secrete, like specific proteins, peptides (fragments of proteins) or RNA.

Artificial intelligence is also often used to detect this circulating tumor DNA, proteins and RNA to diagnose cancer at a much earlier stage.

An example of such a multi-cancer detection test is the Galleri test. This cancer screening test claims to “screen for more than 50 cancers”.

This sounds impressive, but there are various things to take into account when assessing such multi-cancer screening tests.

Let’s take the Galleri test as an example, and what to take into account to see how good such a test really is to track down cancer much earlier.

1. Multi-cancer screening tests do not screen for all cancers

The Galleri test screens for 50 cancers. This sounds formidable. However, there are many cancers. In fact, there are literally hundreds of different types of cancers.

The Galleri test does not screen for many other cancers. For example, the Galleri test does not screen for various brain cancers because they shed limited amounts of tumor DNA into the blood.

2. The sensitivity of the test depends on the type of cancer

The Galleri test cannot detect all cancers with the same high accuracy. It can detect some cancers (much) better (or worse) than others. So its “sensitivity” can differ wildly for the 50+ cancers this test can “detect”.

“Sensitivity” means the ability of a test to correctly diagnose people with cancer (these people are called “true positives”, so people who have cancer).

The higher the sensitivity of a test, the better. For example, a test with a sensitivity of 98% means that the test will detect 98 (true positives) out of 100 people with cancer, missing only 2 people with cancer (false negatives).

The Galleri test has different sensitivities for different types of cancer. Galleri’s sensitivity for some cancers is very low, meaning it’s not good at detecting these cancers.

These are cancers like prostate cancer (a very prevalent cancer in older men), kidney cancer, bladder cancer, breast cancer (the most common cancer in women), and myeloid cancer, among others.

The sensitivity for prostate cancer is only 11.2%, which means this test misses 88.8% of people who have prostate cancer. The sensitivity for bladder cancer is 34.8%, meaning it misses two third of people with bladder cancer (see figure below):

With such low sensitivities, screening for these cancers is quite useless for doctors; you don’t want a test that misses two thirds or even half of all cancers. For a screening test to be acceptable, the sensitivity should be at least 80%, and ideally more than 90%.

The overall sensitivity of the Galleri test was 52%. This is when taking all cancers together and calculating the average sensitivity. This means this test can detect about half of these cancers in people.

For some cancers, its sensitivity is much higher, more than 80% for ovary cancer, colon cancer, esophageal cancer, liver and bile-duct cancer for example. But as discussed, for various cancers, its sensitivity is too low.

Therefore, it’s important to always combine a multiple-cancer screening test like Galleri with other tests that have a much higher sensitivity for specific cancers. I will discuss these tests later on.

3. Less good at detecting early-stage cancers

The sensitivity of a test also depends on the stage of the cancer. Early-stage, smaller cancers are of course less easy to detect than later-stage, larger cancers.

This is a problem, given that we want to detect cancers as early as possible given that the success of a treatment is then much higher.

For the twelve cancers the Galleri test is best at screening for, such as lymphoma, esophageal, colorectal, anal, stomach, liver/bile-duct, ovary, pancreatic, plasma-cell, bladder, lung cancer, the Galleri tests finds only about 40% of stage I cancers, 67% of stage II cancers, 80% of stage III cancers and 95% of stage IV cancers.

So for early stage cancers, it misses more than half of these cancers (actually, 60%). Of course, better to detect cancer at a later stage than not detecting it at all.

Conclusion

Does this mean that a test like the Galleri test is not recommended? The Galleri test can be a useful screening test. But it still has lots of shortcomings, like not screening for al cancers, having only acceptable sensitivity for some cancers, and being less able to detect early stage cancer.

Nonetheless, this test good at screening cancers like liver cancer, bile-duct cancer, neck cancers, esophagus cancer, pancreas cancer, ovary cancer, colon and rectum and anal cancer, cervical cancer, cancers of the urine tract, with sensitivities of more than 80%, especially for later stage cancer.

But for many other cancers, such as prostate cancer and kidney cancer, its sensitivity is too low.

Therefore, tests like the Galleri test should always be combined with other screening tests and methods.

Of course, this will change. The scientists who developed the Galleri test will further improve this test. Many other researchers and companies are working on similar early cancer screening tests. Examples are Freenome, Inivata, Accuragen, Diagu, and many others.

Scientists are looking not only for for mutated circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), but also changes in the epigenome of circulating cancer DNA strands, while also using proteomics (detecting specific proteins and peptides released by cancer cells), transcriptomics (RNA strands released by cancer cells into the blood), and apply ever more sophisticated machine learning algorithms to detect patterns that will allow diagnosing cancer much sooner and with higher sensitivity.

Imagine a future where people go to their doctor (or order a test at home), and provide a little bit of blood (or urine in case of prostate cancer), which is then sent to a lab to be analysed to detect cancer much earlier so people can be treated far more successfully. This is a future we are heading to.

The post Pros and Cons of Cancer Screening Tests like Galleri appeared first on Kris Verburgh.

Rapamycin for Anti-Aging and Longevity

Rapamycin (also called sirolimus or rapamune) is one of the most well-known, researched, and promising drugs for anti-aging and longevity. According to various experts, including Professor Matt Kaeberlein, rapamycin is currently the best drug we have for longevity, significantly better than other drugs, including […]

ANTI-AGING

Rapamycin (also called sirolimus or rapamune) is one of the most well-known, researched, and promising drugs for anti-aging and longevity.

According to various experts, including Professor Matt Kaeberlein, rapamycin is currently the best drug we have for longevity, significantly better than other drugs, including metformin (more about this drug later).

Rapamycin was discovered on Easter Island around the 1970’s; the drug is named after “Rapa Nui”; the name for this island by its original inhabitants. Rapamycin is a complex molecule derived from bacteria that live in the soil, called Streptomyces hygroscopicus (R).

In fact, the typical smell of fertile land after rain comes in part from volatile compounds produced by Streptomyces bacteria.

Around twenty years later, rapamycin was approved by the American Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to prevent organ rejection in kidney transplant patients. Since then, rapamycin has been approved for various other indications, such as liver transplantations, perivascular epithelioid cell tumors (PEComa, a rare tumor that forms in the soft tissues of the intestine, stomach, lungs and other organs), and lymphangioleiomyomatosis, a rare lung disease in which cysts grow in the lungs, lymph nodes and kidneys.

Stents (little coils that go into narrowed, atherosclerotic arteries to open them up) are also coated with rapamycin to prevent them from growing over by tissue when they are put into an artery to widen it.

Rapamycin has been researched for decades, and numerous studies show that this drug can extend lifespan in various species (R,R,R,R), not only in unhealthy or diseased animals, but more importantly, also in normal, healthy animals (R,R,R).

For example, rapamycin increased lifespan in male mice by 23% and 26% in females when started in relatively young mice at 9 months of age (the average lifespan of lab mice is 2 years, so 9 month old mice would be around 35 years in humans) (R).

When started later in life (in 600-day-old mice), rapamycin still had an effect: it increased maximum lifespan by 9% in males and 14% in females (R).

However, some scientists believe that the doses of rapamycin used in most studies are too low, and that even stronger longevity effects could be realized if the doses would be higher (R).

For example, in one study three different doses of rapamycin were administered in young to middle-aged mice (9 month-old) mice (the doses were 4.7 parts per million (ppm), 14 ppm and 42 ppm; ppm means one millionth of a substance, like 1 mg of rapamycin per kg of food, or 1 mg of rapamycin per liter of drinking water).

The lowest dose (4.7 ppm) increased medium male lifespan by 3% and medium female lifespan by 16%. A higher dose (14 ppm) increased medium lifespan in males by 13% and 21% in females. The highest dose (42 ppm) increased medium lifespan in males by 23% and 26% in females (R,R):

Higher doses of rapamycin lead to more life extension

That’s why some researchers recommend using higher doses, like 42 ppm, 140 ppm and even 420 ppm for new longevity mice studies (R).

Other studies, in which higher doses of rapamycin were used also showed larger effects. For example, in one study old mice (20-22 months of age) were injected every other day during 6 weeks with rapamycin (4 mg/kg). The drug was injected intraperitoneally, meaning injected in the abdominal cavity.

Intraperitoneal injection leads to a fast, very high peak of rapamycin in the blood, much higher than when rapamycin is given orally. At the end of the study, 80% of the mice that got rapamycin were alive, compared with only 20% of the control group (R). So mortality was 4 times lower in the rapamycin group:

Considerably less mice that received intraperitoneal injections of rapamycin every other day (4 mg/kg) died 30 weeks after treatment (black line) versus mice that didn’t receive rapamycin injections (dotted line)

In another study mice were injected with rapamycin (1.5 mg/kg) starting at 2 months of age intermittently: they received an injection 3 times per week for two weeks out of every month. At 800 days of age, 54% of the treated animals were alive, compared to 36% of the control animals. At day 900, the results were even more impressive: 31% of the mice that received rapamycin were alive, while only 10% of the control mice were alive (R).

One study examined the impact of rapamycin in obese mice. Mice were put on an unhealthy high-fat diet. After 2 years, 100% of the mice that received weekly injections with rapamycin were still alive, while more then 60% of the untreated mice had died (R):

Mice are put on an unhealthy high-fat diet. After two years, mice that received weekly rapamycin injections are all alive (black dotted line) while about 60% of mice without rapamycin died (blue line)

This does not necessarily mean that humans have to take very high doses of rapamycin. But this does show that results in mice could perhaps be even more impressive when the doses would be higher.

This is why various rapamycin longevity researchers who take rapamycin themselves believe that the doses should at least be sufficiently high enough (I will discuss rapamycin doses for humans later on).

But the dose should not be too high of course. Too high a dose of rapamycin, especially when taken continuously, can have various significant side-effects (which I will also discuss later on).

On the other hand, some fears of rapamycin are exaggerated, like that rapamycin impairs the immune system, increasing the risk of infections (I explain more about this here), or could lead to increased glucose levels and type 2 diabetes (I explain more about rapamycin and diabetes risk in this article).

Rapamycin and cancer

Besides extending lifespan, we see that rapamycin can improve various aging-related diseases, including cancer. This makes sense, given rapamycin curbs various growth pathways in cells, and cancer cells are exhibiting uncontrolled growth.

For example, rapamycin can extend the lifespan of cancer-prone mice (R,R,R):

Rapamycin could also prevent or slow down tumor growth in various other rodent studies (R,R,R).

Rapamycin and heart disease

Rapamycin and similar drugs could also improve heart health.

Mice fed a high-cholesterol or high-fat diet had 48% less plaques in one study (R), and 44% to 48% less plaques in another study (R). “Plaques” are sticky, hard parts forming in our blood vessels, contributing to atherosclerosis.

Cardiac hypertrophy could also be significantly reduced in mice (R,R,R). Often, when the heart has to pump against increased resistance (as can happen when our arteries become more stiff during aging) the heart muscle starts to swell, becoming “hypertrophic”, which impedes the proper contraction and functioning of the heart.

Rapamycin could also improve heart function during aging in mice (R,R,R).

How does rapamycin work? How can it slow aging and extend lifespan?

Rapamycin can slow aging and extend lifespan in various ways.

1. Rapamycin is an mTOR inhibitor

First, rapamycin is an mTOR inhibitor. mTOR is a protein found in our cells. It’s an important “nutrient” sensor which senses nutrients, mainly amino acids. If there are a lot of nutrients like amino acids present in our blood and cells (because we ate a big steak for example, which consists of proteins which are made up of amino acids), this activates mTOR. mTOR then revs up the production of protein (mainly, but also of DNA and lipids), metabolism and growth in our cells.

This makes sense. If there are a lot of nutrients (e.g. amino acids) available, this means there are a lot of building blocks and energy for the cells, so the cells rev up their metabolism, growth and work harder.

However, this activation of metabolism and growth accelerates the aging of cells. For example, cells start to produce more proteins, which can clump together faster, contributing to aging (accumulation of proteins is one of the hallmarks of aging).

Another consequence of having lots of nutrients available, is that cells will maintain themselves less well. They let themselves go. Why should they be frugal, and painstakingly recycle their components and maintain and repair themselves, when there are enough building blocks and energy available? No need to skimp on repair, recycling and maintenance when there are plenty of resources. Compare it with money; some people who have suddenly lots of money splurge on all kinds of things they don’t really need, spending it quickly, living the fast life. On the other hand, people who have little money will live more frugally, be careful what to spend, and will try to recycle stuff for their home or rather repair it than buy new things.

So how does mTOR activation cause less maintenance? It suppresses autophagy for example, which is an important maintenance and recycling process. Autophagy is the breakdown (digestion) of proteins and other cellular waste material. mTOR-induced suppression of autophagy, which is not a good thing, causes more buildup of (damaged) proteins, old and damaged cell components and other problems. If you eat lots of protein, especially animal-based protein, mTOR is activated and autophagy is suppressed.

The opposite happens when we are eating little (e.g. during fasting): autophagy is then upregulated, which cleans up the cell and increases maintenance and lifespan. The cell has to use its resources wisely because it doesn’t know when there will be food again.

Rapamycin can also induce autophagy independent of mTOR. Rapacymin stimulates an important channel on the lysosomes (TRPML1), which activates the lysosomes (R). The lysosomes are small vesicles in our cells which break down proteins and old or damaged cell components – you can consider them as the incinerators of the cells (I explain more about lysosomes and autophagy in the earlier chapter the hallmarks of aging, namely a decline in proteostasis).

2. Rapamycin and mitochondrial health

Rapamycin could also be promising to treat mitochondrial diseases.

Rapamycin has been shown to improve mitochondrial health, both in normal mice (R) and in mice with serious mitochondrial diseases (R,R,R,R).

In one mitochondrial disease model, called Leigh’s syndrome, rapamycin was given to see if it could improve survival of mice with this disease. Leigh’s syndrome is a very serious mitochondrial disorder caused by a defective protein in the “respiratory chain”. This is the “chain of proteins” through which electrons flow (coming from the food you eat, which are then donated to the oxygen molecules you breathe in to form water).

The mitochondrial respiratory chain generates nearly all the energy of the cell, and thus for life to sustain itself. In Leigh’s syndrome, a protein in this chain is not working properly, severely impeding the ability of cells to produce energy. In these mice, rapamycin extended lifespan up to threefold (R).

How could rapamycin improve mitochondrial health?

For one thing, rapamycin can upregulate lysosomal function. Lysosomes are small cell components which break down cellular waste and even whole cell components, like the mitochondria. Each cell can contain hundreds or more mitochondria, which provide the energy cells need to function. These mitochondria, when they are too damaged or worn out, need to be broken down and replaced by new mitochondria. Mitochondria are broken down in the lysosomes, the little incinerators of the cell.

Rapamycin induces the lysosomes to break down mitochondria so that worn-out mitochondria are more replaced with fresh and better functioning mitochondria. Rapamycin can also activate lysosomal biogenesis (the creation of more lysosomes), which is a good thing given cells then get cleared out and maintained better by additional lysosomes (R,R).

3. Rapamycin has epigenetic effects

Rapamycin also impacts the epigenome, and can reduce epigenetic age (R,R). The epigenome determines which genes are switched off and on in our cells, and during aging this mechanism goes awry. Rapamycin can improve the epigenome in a beneficial way, for example by inducing the expression of beneficial genes (R,R,R).

4. Rapamycin improves the microbiome

The gut microbiome are all the bacteria in our intestines. These 40,000 billion bacteria have a large impact on our health and well-being by processing and secreting thousands of substances, of which many enter our bloodstream and impact our immune system, metabolism, and brain.

However, during aging, the microbiome deteriorates, leading to bacterial overgrowth, increase of “virulent” (bad) bacteria, and damage to the gut lining (“leaky gut”) for example.

Rapamycin can positively impact the bacterial diversity in the gut, or inhibit bacterial activity. In one study in mice, rapamycin increased the mount of segmented filamentous bacteria, which are “good” bacteria that do not tend to secrete unhealthy substances and that strongly cling onto the gut wall, which might strengthen the gut lining and positively impact the gut immune system (R).

Interestingly, another well-known longevity-candidate, metformin, has also been shown to significantly impact the microbiome, by also modulating or tempering bacterial activity in the gut.

Other effects of rapamycin on health

Given these and other effects of rapamycin on the body, it’s not surprising that rapamycin can improve stem cell health (R) and reduce senescence (R), and extend lifespan.

Learn more about rapamycin:

- Does Rapamycin Cause High Glucose, Lipids and Diabetes?

- Does Rapamycin Increase Infection Risk?

- How Does Rapamycin Work? Overview of Rapamycin Lifespan Extension Studies

- Rapamycin for Anti-Aging and Longevity

- How does rapamycin work? How can it slow aging and extend lifespan?

The post Rapamycin for Anti-Aging and Longevity appeared first on Kris Verburgh.

What Is The Best Biological Age Clock?

Epigenetic clock tests are probably one of the best methods to assess your overall health, disease risk, mortality risk, and rate of aging. Epigenetic tests seem to perform far better than genome tests (DNA) tests, which have been somewhat of a disappointment given they […]

ANTI-AGING

Epigenetic clock tests are probably one of the best methods to assess your overall health, disease risk, mortality risk, and rate of aging.

Epigenetic tests seem to perform far better than genome tests (DNA) tests, which have been somewhat of a disappointment given they are not that insightful to get a better picture of your health, disease and mortality risk (however, I will explain later on why some DNA tests can still be useful).

Biological age versus chronological age

Epigenetic tests or “epigenetic clocks” determine your “biological age”.

Your biological age is your “real age”: it’s how old your body really is. The higher your biological age, the higher your risk of aging-related diseases and dying.

For example, if someone is 50 years old chronologically, but biologically 58 years, it means this person is unhealthier and older for his age, and has a higher risk of aging-related diseases and dying.

Various epigenetic clock tests have been developed (R,R,R,R), and often are further improved upon, while many more new epigenetic clocks are in development.

How do epigenetic clocks work?

Epigenetic clock tests look at the methylation patterns on our DNA.

Parts of our DNA are methylated, while other parts are not methylated.

When DNA is methylated, it means a “methyl group” is put on DNA – a methyl group is a small molecule composed of one carbon atom (C) and 3 hydrogen atoms (Hs).

When a gene is significantly methylated it means it’s covered by a lot of methyl groups, which hinders the copying machinery to reach this gene to translate it into protein. So this gene is “silenced” (in most cases; it’s also possible to activate genes via methylation).

Methylation is an important part of how the epigenome works. It also plays an important role in aging, which also explains why epigenetic clocks are very interesting to measure biological age and rate of aging.

I explain more about the epigenome and its role in aging here.

During aging, our methylation patterns change. We see that large regions of our DNA become less methylated (“hypomethylation”) while specific regions (including regions that encode for gene activity) become overmethylated (“hypermethylation”).

Epigenetic tests look at whether specific regions in the DNA are methylated or not. It can correlate this methylation pattern with your biological age and overall health. People who are epigenetically or biologically older have other methylation patterns than biologically younger or healthier people.

Epigenetic clocks need to be trained on data: methylation data and specific biomarkers of health and disease and mortality to correlate the two.

Researchers need to chart thousands of places in the DNA to see if these places are methylated or not, and then correlate these methylation patterns with health and disease biomarkers, or with chronological age.

A DNA strand (starting at the bottom) is methylated and then wrapped around histone proteins (yellow structures), which further condense into chromatin, forming chromosomes.

Different types of epigenetic biological clock tests

There exist different kinds of epigenetic clocks. One way to classify them is whether they measure biological age or the rate of aging.

Another way to classify them is whether they are first, second or third generation clocks.

1. Rate of aging clocks

These epigenetic clocks measure how fast your body is currently aging (your rate of aging).

They measure how fast your biological clock is currently ticking.

For example, a result of 0.85 would mean you would only age 0.85 years for each chronological year. That’s good. Unfortunately, many people have a rate of aging test results higher than 1, which means they age too fast.

An example of a rate of aging clock is the DunedinPACE clock (R).

2. Biological age clocks

These clocks measure how old you are biologically. They measure the time on the clock (“how late it is”).

So while “rate of aging clocks” measure how fast the dial is currently ticking, “biological age clocks” measure the current time. The later the time, the older your body is.

Ideally, a good biological age clock measures all the damage your body has accumulated during your lifespan until now.

If you led a generally healthy life, your biological age will be lower than your chronological age.

For example, you will be epigenetically (or biologically) 45 years old despite chronologically being 53 old. This also means that your risk of diseases and dying is lower than what one would expect for your age. That’s good!

Another way to categorize epigenetic tests is by what they actually measure. This leads to the following types of tests:

3. First generation biological age clocks

The first generation of epigenetic clocks correlated methylation patterns with one’s chronological age (R,R).

But why would you want to use the epigenome to find out your chronological age, given you just can find out someone’s chronological age by looking at the birth date on their passport (much cheaper and faster!).

The reason is that chronological age is also a crude biomarker of death and disease. We all know that the older you are chronologically, the higher your risk of getting a heart attack, cancer or dying.

In fact, every 8 years, your risk of dying doubles. So someone who is 38 years old has double the risk of dying than someone who is 30 years old, and by the time you are in your eighties you have a very, very high risk of dying, meaning you can drop dead almost any moment.

So “chronological age” is the easiest biomarker of death and health to come by – everyone knows their chronological age. Therefore, scientists set about correlating epigenetic methylation patterns with one’s biological age.

For this, they correlated epigenetic data (methylation patterns) with the chronological age of thousands of people. This way, they could correlate methylation patterns indirectly with one’s risk of dying (given the higher your chronological age, the higher your risk of dying).

Interestingly, if you then take just one individual, and look at her methylation pattern, one can see how much it deviates from this “average” or “general”’ epigenetic pattern that was found when trained on large groups of people. The more this individual epigenetic pattern differs from the average, the higher or lower the biological age or risk of dying.

For example, if one is 60 years old according to her methylation pattern, while chronologically she is just 53 years old, this means she has double the risk of dying (given every 8 years one risk of dying doubles).

In other words, the “perfect” chronological age clock would always perfectly predict your chronological age. But it doesn’t, given some people will have methylation patterns that make them look younger or older than others (“the average” methylation pattern).

These “chronological age” epigenetic clocks were among the first generation clocks. Examples are the Horvath 2013 clock (R) and Hannum’s clock (R).

So this first generation epigenetic clock tried to predict your risk of dying by predicting your chronological age by looking at methylation patterns. However, better than correlating these clocks with chronological age would be to correlate them to actual mortality or disease risk.

However, mortality data is difficult to come by. One would need to analyze the epigenome from people and wait until they die, which is very costly and time consuming. Or one could look into databases of stored blood (of people of which their birthdate and date of death are known) and epigenetically analyze their blood. But this would also be time consuming and costly.

So scientists set about trying to indirectly measure mortality (and disease) risk. And this brings us to the second type of epigenetic clocks.

4. Second generation biological age clocks

These clocks measure disease or mortality indirectly, for example by looking at specific substances in the blood which are associated with disease risk or mortality risk.

Examples of such substances are glucose levels, CRP levels (a protein associated with inflammation), GDF15 protein levels, TIMP2 protein levels, etc.

Scientists have access to blood samples or data stored in data banks which measured the levels of these substances in the blood of thousands of people.

They then look at which epigenetic patterns are correlated with the blood levels of these substances, which in turn correlate with disease or mortality risk.

For example, people with high levels of glucose have a higher risk of dying. Having higher levels of glucose is also correlated with specific epigenetic patterns. So an epigenetic clock can be trained to figure out which epigenetic patterns are correlated with higher levels of glucose, and thus also with a higher risk of dying.

Examples of these second generation clocks are Horvath’s DNAmGrimAge clock (R,R), which has been trained to look at methylation patterns correlating with seven blood biomarkers, namely levels of adrenomedullin, beta‐2 microglobulin, cystatin C, growth differentiation factor 15, leptin, plasminogen activation inhibitor 1 (PAI-1), and tissue inhibitor metalloproteinase 1 (TIMP1). This clock also takes into account some other markers of health and mortality, like smoking and sex.

Another clock is the Horvath-Levine’s DNAm PhenoAge clock (R), which looks at 9 blood biomarkers (creatine, CRP, red blood cell distribution width (RBCDW), total leukocytes, lymphocytes, albumin, glucose, mean cell volume, alkaline phosphatase) and some other biomarkers of health, disease and mortality.

These second generation clocks have been shown to more accurately predict mortality risk and disease risk than the first generation chronological age clocks.

Of course, this is a bit of a circuitous and indirect way of measuring health and disease and mortality risk. A more direct way would be to actually measure how healthy you are.

This brings us to the third generation of epigenetic clocks.

5. Third generation biological age clocks

These clocks take into account various biomarkers of disease and health, such as grip strength, brain size, walking speed, dental health, cognitive functioning, blood tests (e.g. measuring Hb1ac, LDL and HDL cholesterol), and so on.

These biomarkers, especially when taken together, paint a much better picture of one’s overall health and mortality risk than just looking at a few blood proteins or your chronological age, like the earlier generation epigenetic tests.

Scientists then try to figure out which epigenetic patterns correlate with these biomarkers. This way, they then can just look at the epigenetic pattern of an individual to predict their health or mortality risk without having to actually measure all these biomarkers.

Examples of such clocks is the DunedinPACE clock (R).

What is the best epigenetic biological age test?

The best epigenetic clock would be one that is trained on many powerful biomarkers of health, disease and mortality risk.

These can be real, physiological biomarkers, like the size of your brain (during aging, the brain shrinks), blood pressure, weight, dental health, facial health (if you look older, changes are your body is also older), balance, grip strength, gait speed, working memory, reasoning, and so on. It should also incorporate other biomarkers, like blood biomarkers (HDL cholesterol, inflammatory proteins, glucose levels, and so on).

One of the few clocks that actually measures various of such biomarkers, is the DunedinPACE clock. This clock has been the result of scientists tracking the health of around a thousand people for decades, regularly measuring their grip strength, dental health, brain size, memory, facial aging, and so on. All these measurements paint a more accurate picture of one’s health and biological age.

The DunedinPACE is a rate of aging clock: it tells how fast your biological clock is currently ticking. That’s good.

However, you would also want to know the time on the clock (how much time has already passed). For this, you need a biological age clock. A decent biological age clock is the GrimAge clock (a second generation epigenetic clock).

So ideally, one does two epigenetic tests: one test to measure your rate of aging (how fast the clock is ticking now), and another to measure your biological age (the time on the clock).

Other things you would preferably like to see in a good epigenetic clock:

- Ideally, the clock is trained on data of large groups of people, like thousands of people or more. The larger the testing group, the more accurate the clock can be.

- Ideally, the epigenetic clock is published in peer-reviewed journals, and its data and algorithms are open source so the clock can be checked by other, independent scientists. Various epigenetic clock companies do the opposite: they developed in-house epigenetic clocks and do not share their data and algorithms with other scientists, so it’s more difficult to see how these clocks work, and if they are actually accurate and predictive.

- They have high test-retest results. This means if you use these clocks to measure one’s biological age, and then quickly do this test again, the results should be very similar. Currently, some epigenetic clocks have low test-retest results: this means when you take this test and then retest an hour or day later, the results can differ wildly, which is not good of course.

- Proper epigenetic clocks are correlated with both disease and mortality risk. So they tell you your risk of diseases, and your risk of dying.

- They use state of the art machine learning and/or mathematical and statistical methods to properly correlate epigenetic patterns with health, aging and mortality. Lots of earlier clocks use more simple methods, like linear regression, while newer clocks use machine learning and improved statistical methods.

The future of biological age clocks